U.S. Navy destroyers without physical throttles?

Touchscreens work well for many tasks at a boat helm (and elsewhere), I think, but a touchscreen throttle never even occurred to me until I read about the Navy “reverting to physical throttles” on warships like the USS John S McCain. Holy cow! Why the heck did we deprive destroyer drivers of the excellent (electronic) control interface known as a throttle lever, and why is Wired magazine mispresenting the “reversion”?

I’d be very hesitant to criticize a destroyer’s helm ergonomics because I’ve never experienced a vessel even remotely similar, but you too may mutter “Duh!” after reading this U.S. Naval Institute’s reporting. Of course the helmsmen would like familiar throttle levers instead of — or maybe in addition to — awkwardly reaching for the software version on those big touchscreens, and it’s quite hard to understand how actual physical throttles got left off these vessels in the first place.

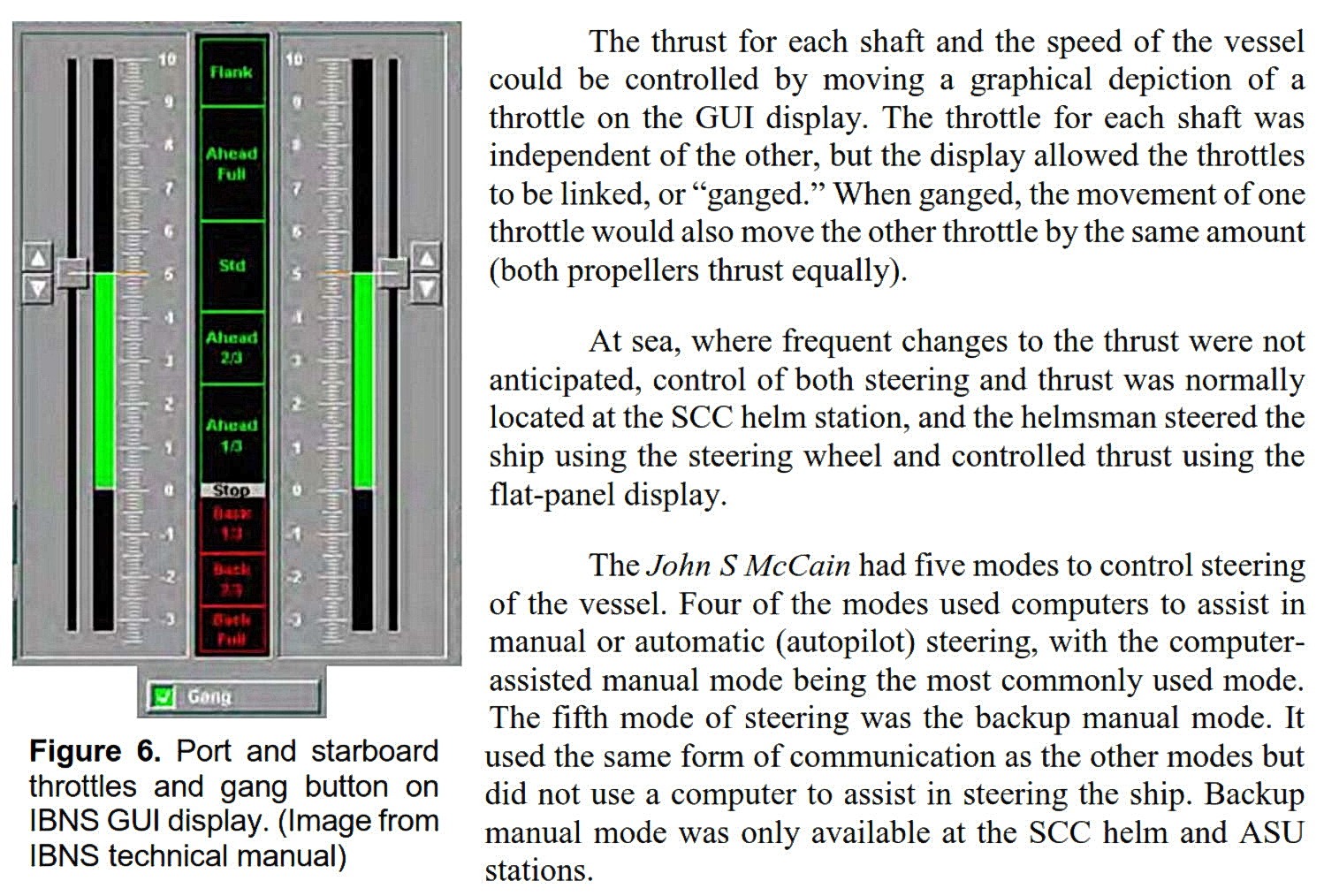

But let’s note that touchscreen throttles were not a major factor in the deadly collision caused by the McCain off Singapore. The NTSB’s thorough accident report (PDF) does cite confusion about how steering control was switched among helm stations via the graphical user interface (GUI), but pins the main blame on “a lack of effective operational oversight of the destroyer… which resulted in insufficient training and inadequate bridge operating procedures.” Command heads rolled.

Despite the wisdom of the NTSB (National Transportation Safety Board), it’s no longer surprising when some folks blame electronics for human errors. But it’s shocking that a great source of tech writing like Wired magazine published “NO MORE SCREEN TIME! THE NAVY REVERTS TO PHYSICAL THROTTLES.” The entire article is predicated on the completely mistaken notion that the Navy is replacing the touchscreens with normal (electronic) throttle hardware. So “NO LESS SCREEN TIME!” would be a more truthful headline!

My thinking: electronics aren’t going away, and shouldn’t, but that certainly doesn’t mean that we must always relate to them via touchscreens. Heck, the excellent single-lever throttle/shift at each of Gizmo’s helms are not needed to leverage stiff control cables — the boat has been “fly by wire” for 20 years. But the lever is tactile, visual, it’s always in the same place, and it doesn’t change functions. I’d certainly consider additional control like the Dockmate that Ben Stein is testing, but would never ever remove the levers.

Come to think of it, I’d also consider a smartphone with a knob and curser controller for the many tasks where they’re better than touch, except it wouldn’t fit in my pocket. What’s your thinking?

Electronic warfare is becoming an everpresent concern by potential enemies and even from our own devices. During theses stressful conditions, I suspect, that the Navy wants to be 110% certain their throttle controls will withstand any sort of friendly or unfriendly wireless signals. I wonder what their intentions are for steering and shift controls will be?

As a product developer and systems integrator in the professional marine electronics industry, I think Ben’s analysis is spot on. My philosophy since many years has been in line with the points brought up by Ben – in short, I would summarize my approach something like this: technology is a means – not an end in itself; always design with the end in mind, not the means.

It seems that it’s easy as a systems developer to fall into a mindset of almost sheepishly adopting new technologies simply because they’re new, subconciously assuming that “new” must equal “better”, jumping on any bandwagon that has “TREND” written on its side. Laziness might also be a factor; in today’s world of high-complexity mass-market technology it is often much easier to do things the way they’re done in other mass-market products rather than optimizing things for the marine use case.

Coming from the professional side, I tend to be even more conservative than Ben regarding Human-Machine Interfaces (HMI). I’m usually very skeptical of touchscreens for anything that could potentially need interacting with while at sea. In rough weather, they can be a nightmare, trying to touch the right thing while avoiding touching all the wrong things.

Another truly important aspect in my experience is that physical knobs, levers and switches can be maneuvered without looking at them. In a stressful situation, it should go without saying that you must be able to operate steering and engine controls without LOOKING at the controls, i.e. bringing your attention away from the situation outside, around your vessel.

This, in my opinion, applies to almost all controls at a helm station. TCPA alarm going off while coming alongside? Having to look down at the touchscreen and precision-point at a soft button wouldn’t be great. Pressing a physical “Alarm acknowledge” switch that your muscle-memory can locate without looking? A lot easier.

Getting into finer details, the huge trend of using rotary encoders (knobs that go around and around with no end stops) is problematic for similar reasons. Imagine you’re in a rescue situation, for example; manouvering around a person in the water. There are intermittent radio conversations on your VHF that’s turned up too loud, so that you can’t hear your deckhand trying to communicate with you from outside. With the popular rotary encoders, you have to look at the VHF while turning the volume knob frantically until the volume bar is down to zero.

With a classic knob, you would simply reach for it (without taking your eyes off the person in the water) and turn it all the way down until you feel the stop. Things like this should be no-brainers for manufacturers in my humble opinion – sadly, that doesn’t seem to be the case.

I could go on and on, but I’ll stop here for now and leave the rest for a future book on marine HMI principles…

Thanks, Mark, and I’m sure I’m not the only one interested in your book.

Good article Ben. Not sure if you made it through the entire report or not, but it’s definitely worth reading for anyone in command of a vessel of any size. There are a lot of lessons to be learned. The lack of systems knowledge, experience, and proficiency demonstrated by multiple individuals was frankly disturbing. They essentially lost control of a perfectly good ship through nothing more than a transfer of control between two stations – a transfer the the Board found should probably not have been initiated in the first place during close quarters maneuvering in a congested seaway. The resulting chain of errors is too lengthy to go into here, but yes, to your point – physical throttles would be a no brainer for a helmsman, and likely would have precluded both the unintentional asymmetric thrust and perhaps the collision as well.

Current recreational electronics and helm design leave a lot to be desired from an ergonomic standpoint – but that doesn’t excuse ignorance of how they’re designed to work. I’ve seen too many mishaps and close calls created by folks who didn’t understand how to safely use the equipment they already have. The McCain was another tragic example of that.

While not directed at touch screen tech, an article by me appeared in a recent PassageMaker magazine related to the two destroyer accidents. I have years of experience on the bridges of virtually every US Atlantic Fleet destroyer and some Pacific Fleet units unti to 2012 and well as a long career in the Navy handling a number of different ship types, mostly steam powered. I believe in technology as a means to an end, and Navy bridges can certainly benefit. On my own trawler and now Mainship Pilot, I enjoy adding technology where it helps, but touch screens, especially in smaller craft are a hazard in my opinion. I just read an article claiming the Navy is going to change the big ECDIS display up against the front of the bridge in DDGs where the OOD can easily access it from touch screen to some other system, presumably trackball. I would guess that is because its placement lends itself to accidental or unintended actions with the touch screen. Also, destroyers can indeed bounce around in heavy seas just like my trawler did in 4-5 footers making a touch screen a real effort to control well.

Thanks, Rich, and happy to add that I found your PM article online:

https://www.passagemaker.com/trawler-news/rich-gano-analysis-navy-collisions

I’d also like to add that just about every major brand touchscreen MFD can be controlled by a remote pad with buttons and knobs, if they are not already part of a hybrid interface design.

Rich, I just read about your frustration with cluttered AIS displays and wonder if you’re familiar with how Vesper Marine handles it? I firmly believe that the problem is not vessels leaving their transponders on 24/7, which isn’t likely to change anyway. The problem is crude target display and CPA/TCPA alarms, and Vesper shows how it can be done much better, I think.

No, Ben, I am not familiar with Vesper’s handling of this issue. I am very glad that they are though. Do you have a link for this? In the meanwhile, I will poke around to find information. Thanks.

Do you have a link for this? In the meanwhile, I will poke around to find information. Thanks.

Well, over the years I’ve written about several forms of Vesper WatchMate AIS display and alarm handling, but the core principals of highlighting truly important targets and allowing users to set up different alarm modes for different situations remain the same:

https://panbo.com/?s=vesper+watchmate

Thanks, that is helpful. I have an older Furuno VX2 Navnet system which lets me do a little bit of configuration for the AIS like limiting the alarm for collision-imminent vessels to a short range to keep the alarm siren from sounding all day long.

The NTSB report is a very good read and is surprisingly damning of the Navy in several dimensions. Adding fly-by-wire throttles to the steering stations is probably a good idea but won’t get at the root causes of the two destroyer collisions – overworked, undertrained, inexperienced crews are going to make mistakes.