“Practical Navigators” — when olde Salem MA met the paper(chart)less future

The following is my June 2002 electronics column for Power & Motoryacht magazine, but I find it still relevant while also documenting a very memorable experience

The Navigator of the United States Navy does not mess around. Addressing a bow-tie-speckled crowd of New England yachtsmen and nautical history buffs, Rear Admiral Richard West passionately described the “technological explosion” that is blowing apart the grand traditions of marine navigation, and his commitment to an all-digital future. When asked the inevitable question about paper charts, he grinned mischievously and said, “We’re going to throw them all overboard!”

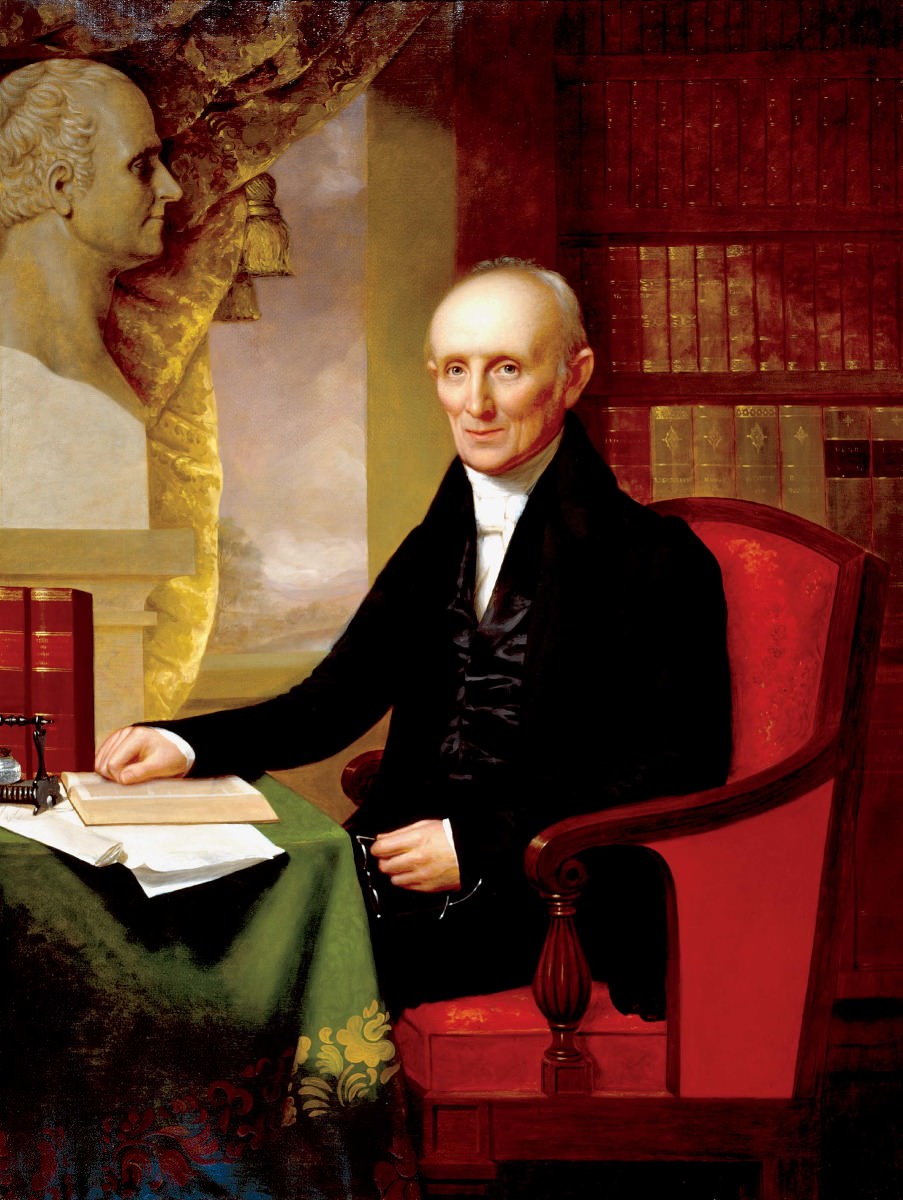

This is radical talk, particularly given the context of the Admiral’s presentation. The occasion was a 227th birthday party for Nathaniel Bowditch, arguably our nation’s greatest navigator, and was held in his now ultra-historic hometown of Salem, Massachusetts. The party kicked off the Bowditch Bicentennial, a yearlong celebration of the man and his signature work, The American Practical Navigator, first published in 1802. The book, usually just called Bowditch and continuously updated through more than 75 editions, is considered the ultimate authority on matters of navigation aboard most ships and many serious yachts.

Bowditch was truly remarkable. By the time he went to sea at 21, he had taught himself advanced mathematics and astronomy, along with at least a dozen languages needed to pursue his voracious intellectual appetite. He already understood the era’s intensely complex methods of navigation, and on his first voyage was finding mistakes in the standard British tables. By 1802, he had developed a “simplified” technique for taking “lunar distances”, then the best system for determining longitude before accurate chronometers were affordable aboard merchant vessels. Even “simplified” lunars make regular celestial navigation look like first-grade arithmetic. Nonetheless, Bowditch vowed to “put down in the book nothing I can’t teach the crew,” and supposedly every member of that crew, including his cook, could take a lunar observation and plot the ship’s position.

In an age when lives and cargos were commonly lost due to navigation errors, Bowditch’s genius and ability to express himself had a significant impact on the safety of sailors and the economic development of our nation. The value of his work did not go unnoticed, and the first U.S. Naval Hydrographic Office purchased the copyright to The American Practical Navigator in 1868. That organization, now called the National Imagery and Mapping Agency (NIMA), continues to update its text, and will début the 2002 edition at the Salem Maritime Festival in July. The latest Bowditch will weigh in at about 1,000 pages, and will include a CD-rom; no doubt, it will thoroughly cover the science of marine navigation, with emphasis on traditional techniques and tools to practice them. {NIMA became the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, or NGA, in 2003}

In fact, Bowditch is virtually required equipment aboard all U.S. Navy and Coast Guard vessels, and Admiral West is intimately familiar with its pages from his many years as a navigator and captain aboard surface ships. In part, that’s why so many traditional sailors are a bit startled by his enthusiasm for the most modern of tools. And I’m not just referring to the history buffs gathered in Salem; apparently a common reaction to West around the fleets is: “Go to sea without paper charts? Are you crazy?” Mind you that, despite rumors to the contrary, celestial navigation is still actively practiced in the Navy, and lunars weren’t actually dropped until the early 1900s. A cautious, traditional approach to new navigation technologies has always served well.

Of course, Admiral West is not crazy. His position as Navigator of the Navy is a serious mandate, not an honorary title; it was created just a couple of years ago when the service realized that many of its parts were independently developing electronic charting systems and sought an overseer. West was already, and remains, Oceanographer of the Navy, responsible for nearly 4,000 personnel who collect and disseminate massive amounts of cartographic, meteorological and other data. His understanding of geospatial information and services (GIS) made him an obvious choice to lead the transition to digital navigation.

And leading he is, faster than expected. The concept of a paperless Navy is now an accepted fact, with full implementation planned for 2004. Captains will have some leeway about when they actually dispense with paper backup, but Admiral West argues well about why they should. He believes that traditional navigation techniques will only give a false sense of security as users become more used to the power of full electronic charting. Pulling out a roll of unfamiliar paper charts when the going gets rough is just not going to cut it. Of course, “when the going gets rough” is considerably more complex for a fleet navigator in warfare than for any of us recreational boaters.

Behind Admiral West’s full embrace of digital charting is a determination to make it absolutely reliable and incredibly powerful. The Navy is conducting its own charting software and hardware development program, and making unclassified portions of it public at www.navigator.navy.mil {no longer online and nothing similar found, 2023}. The basics are familiar to anyone who has used PC charting programs, but beyond the basics, well… wow. Picture hardened server-size computers connected with fiber optics; dual frequency military GPS backed up by inertial systems; any and every sort of data overlaid on charts; and that’s just the unclassified part.

Meanwhile, NIMA is putting together a seamless worldwide database of vector charts. Steve Hall, Associate Director of the agency’s Maritime Safety Information Division, says, “Admiral West is an out-of-the-box forward thinker! He’s leading the Navy into the digital age, and we’re going to help him.” The database, known as the Digital Nautical Chart (DNC), is rich in layers and detail, and has been a massive undertaking, involving the conversion of paper and electronic data from the hydrographic offices of many nations, and the development of systems to keep it updated efficiently and quickly.

If you go to www.nima.mil {now www.nga.mil} and look around the Maritime Safety pages, you’ll find information about the DNC, and much more. Hall and NIMA also deserve credit for forward-thinking; they’ve actually been providing valuable navigation information online to the public since 1983, first by bulletin board, then by Web. Today on their site you’ll find everything from Great Circle Calculators to Piracy Reports to a downloadable version of Bowditch, all for free. There has even been talk that NIMA might distribute the DNC as open data for the benefit of all mariners, but that is unlikely due to copyright issues.

No matter, all this development will benefit recreational boaters in due time. There is always a technological trickle-down; remember where GPS came from in the first place. Some third-world hydrographic offices are now better able to provide vector chart data after working with NIMA. Somewhere being tested in secret is some nifty navigation tool that we will get our mitts on eventually. Perhaps more important is the leadership that men like West and Hall are providing. Like Nathaniel Bowditch, these are true American practical navigators – skilled in the traditions, but open to new technologies, if they work. There’s much to be learned from all these men, and much to be proud of.

PS 7/19/2023: NIMA/NGA still offers the latest 2021 edition of The American Practical Navigator and many other useful publications as free PDF downloads. Enjoy!

So what happened to RADM West’s major overhaul of Navy nav systems? Well, apparently it took until 2011 to get the Integrated Bridge and Navigation System (IBNS) onto the first ship and now there are at least 18 IBNS variants causing difficulties for crew moving from ship to ship, even of the same class:

https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2023/may/fleet-needs-common-bridge-navigation-system

One of the major IBNS issues mentioned in that article involves the collision of the USS John S. McCain with a tanker off Singapore in 2017, discussed here:

https://panbo.com/u-s-navy-destroyers-without-physical-throttles/

Note that oddball touchscreen engine controls have little to do with the deep digital charting that RADM West advocated. In fact, he retired from the Navy shortly after I wrote this article and seems to have gone on to a distinguished second career in ocean research and education: https://www.linkedin.com/in/dick-west-0a476443/

I was a displacement am saddened by the demise of my paper charts … in spite of POD availability. Just old I guess

I’ll be using paper charts while they are still available, the vessels i work on nearly all (not all) have ECDIS fitted, there ‘ok’ but for a complete overview of an area you cannot beat a full chart table width Admiralty paper chart.

It’s interesting to note that the British Admiralty originally set a timeline for the sunset on paper charts for 2026, that has now been revised to ‘2030 at the earliest’.

Bowditch was required reading for me as well in 1985. To add to the paperless chart history. I was employed as a design-engineer at DataMarine (1985-1990). DataMarine launched a product called ChartLink (1989?) it was a Loran based chart-plotter, small CRT display, with track-ball curser control, and digitized marine charts stored on memory cards. Archaic technology by today’s state-of-the-art, but the future of navigation was clear to a few people in late 1980’s.

And brings back some humorous memories of testing ChartLink s/w out in Buzzards Bay with my DataMarine colleagues 😉